Text by by Nicole Ziza Bauer

Images by Tori Dickson

Archival courtesy of The Santa Monica Pier Corporation

It’s September 9, 1909. A boisterous parade flows from Santa Monica City Hall to the beach, where foot and swimming races are accompanied by live music. A tableau vivant depicts Queen Santa Monica defeating the great Rex Neptune. A naval flotilla dots the bay, anchored for just this occasion, and fireworks dazzle crowds by nightfall. It is a day of city-wide celebration—all for a brand-new sewage line running the length of a concrete pier.

It’s hard to imagine that the most Instagrammed location in Los Angeles, according to 2018 to 2019 geotag numbers, had such origins. Yet that humble beginning is exactly what transforms the Santa Monica Pier into something more than meets the eye. Its history is checkered with iconic characters, wild acts of nature, and even a dramatic political campaign worthy of its own play.

“The history of the pier is based upon the contributions of people who have made it special over the years, and I love to tell those stories,” explains James Harris, interim executive director of the Santa Monica Pier Corporation and author of Santa Monica Pier, A Century on the Last Great Pleasure Pier. “Otherwise, this would just be a bunch of planks hanging over the ocean.”

The history of the pier is based upon the contributions of people who have made it special over the years… Otherwise, this would just be a bunch of planks hanging over the ocean.

James Harris

Originally built to solve the city’s growing sewage problem, the pier’s primary function was to funnel waste 1,600 feet from a treatment plant at its eastern end out into the ocean, a service that ended by 1928. But what people were really celebrating on that day in 1909, Harris points out, was the fact that the pier was only the second in the world, preceded only by one in Atlantic City, to be made entirely out of concrete. “It was considered an engineering marvel for its time,” he says.

Harris’s own history with the pier began in 1989, when he started working as a bartender at the Boathouse Restaurant (where Bubba Gump Shrimp Co. stands today). He became intrigued by stories told by “old timers,” as he calls them, pier regulars who weren’t tourists and would share memories of how the area used to be. It was through them that Harris learned of a colorful crew of citizens who banded together in 1972 to save the pier from destruction. He later detailed that story in his play, “SAVE THE PIER!” which recounts when the Santa Monica City Council approved plans for a developer to tear down the pier and create a manmade, resort-filled island. The community fought back, and the pier was saved.

Harris’ interest in the pier grew as he was promoted to general manager of the Boathouse and eventually became the weekend activities coordinator for the Santa Monica Pier Restoration Corporation (as it was known in 2003). In addition to writing the pier’s official history book, he created docent-led tours. Most recently, those tours have evolved into Secret Stories, an app that brings the pier’s history to life and allows users to immerse themselves in the story of how a basic public utility grew to welcome more than 10 million visitors a year. Its puzzles, riddles, and clues unlock lesser-known elements and characters of the pier’s century-long identity.

Take Captain Olaf C. Olsen, a Norwegian immigrant who settled in Santa Monica in 1925. Olsen was a beloved regular of the pier, which had quickly become a local fishing hub, and he frequently operated barges, day-boats, and water taxis from it. Fearing that commercial fishing would wipe out the local ecosystem, he fought to ban net fishing in the bay, a statute which continues to this day. His likeness inspired another well-known sailor: the spinach-loving Popeye created by cartoonist and Santa Monica resident E.C Segar. One look at Olsen’s photo in the Secret Stories app, and it’s impossible to mistake the resemblance.

While the pier’s celebrated cement blocks were replaced with wooden piles due to rust in 1919, public enthusiasm only increased over its first decade. The evolution from fishing community to world-famous amusement pier can be credited to entrepreneur Charles I.D. Looff, a legendary wood carver who built the wooden carousel at Coney Island and crafted more than 40 carousels in his lifetime. He leased the land immediately south of the pier and built what would become the Looff Pleasure Pier—an addition to the original—in 1916. Just one year later, he had developed it to include the Hippodrome carousel building (now registered as a National Historic Landmark), the Blue Streak Racer rollercoaster, the Bowling and Billiards Building, a fun house, a picnic pavilion, and other thrill rides like the Whip and the Aeroscope.

After Looff’s death in 1918, the amusement side of the pier changed ownership several times, finally closing its gates in the 1930s. The pier faded into the background. It wasn’t until the 1970s that local interest in the landmark resurfaced, as recounted in Harris’s play.

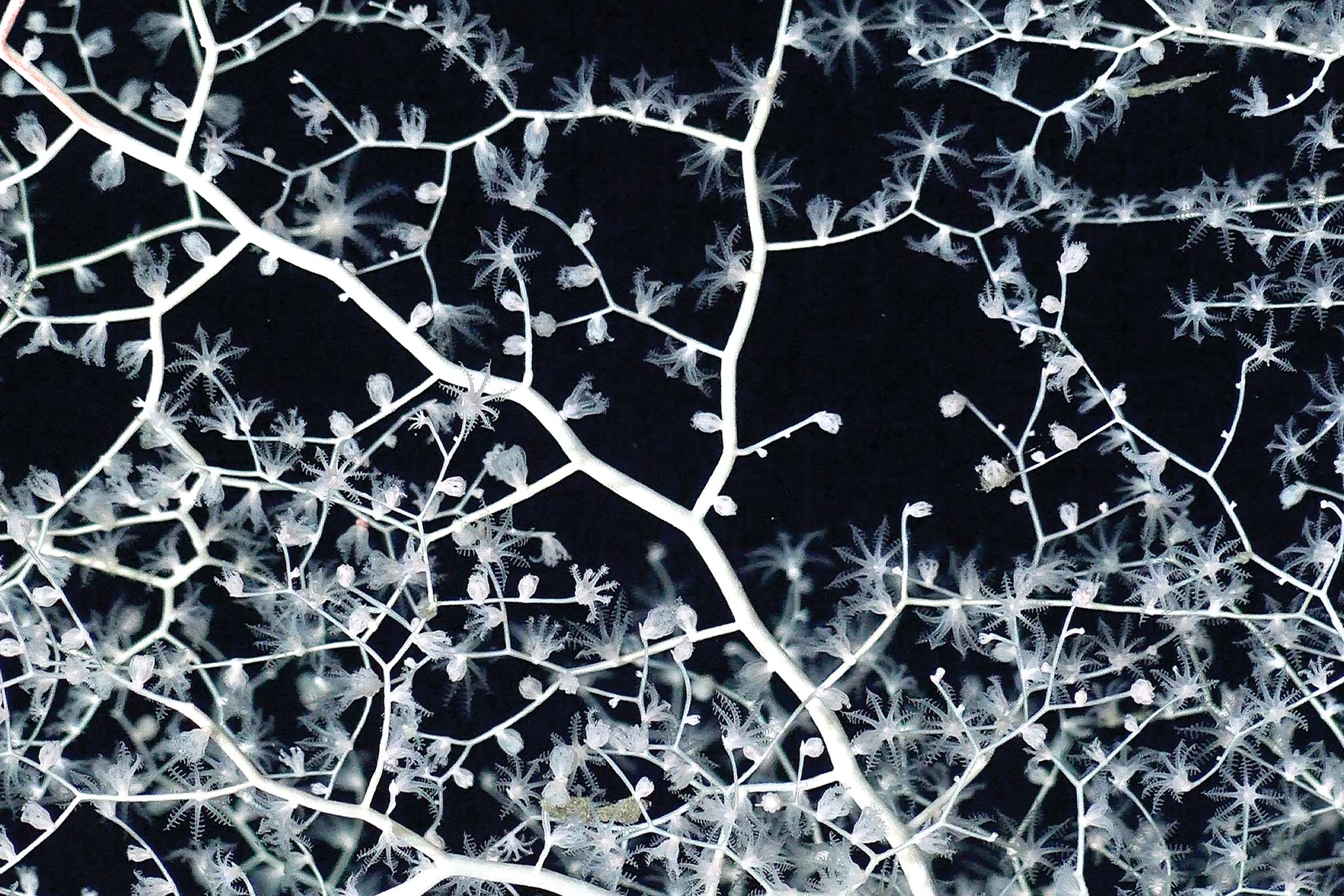

Then, in 1983, a storm sparked by El Niño took out the entire western half of the pier. “That’s when the reimagination began,” Harris says. With revitalized city support, Pacific Park opened in 1996. Soon followed the aquarium, the solar-powered Pacific Wheel Ferris wheel, a trapeze school, and other games and restaurants.

While the pier now has a modern feel, its heavy nostalgic roots haven’t been erased. “We still have pigeons running around and sand worked into the buttons. We’re a little gritty, as we like to say,” says Nathan Smithson, Director of Marketing and Business Development for Pacific Park. “But that’s what makes the pier interesting. There are so many unique things that have been invented at the pier or near it … beach volleyball, Popeye the sailor man. So, for anyone looking for that authentic California experience, know that it can be had here.”