Four book club organizers from across the country share insights on curation to accessibility. Consider this your starter pack to congregating your own literary haven.

Text by Mitchell Kuga

Images by Alohawares

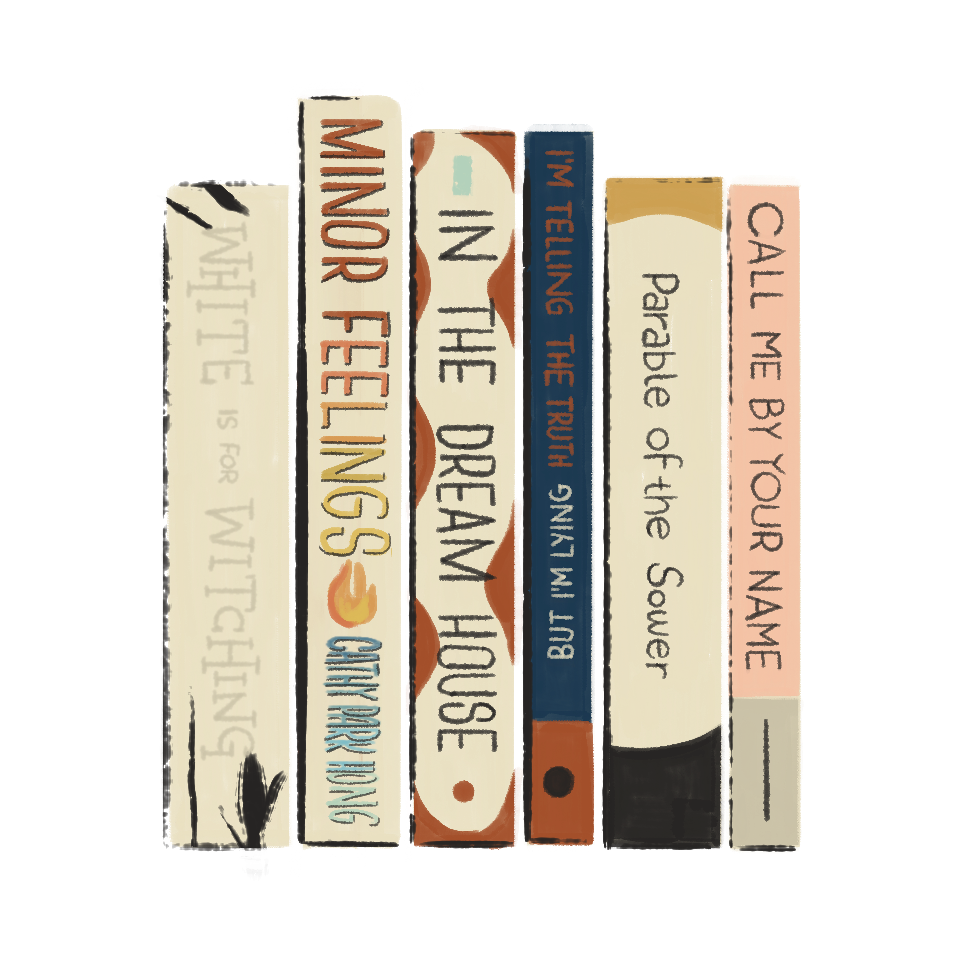

When I finished Cathy Park Hong’s Minor Feelings: An Asian American Reckoning, I held the book to my chest and let out a long exhale. With a lyrical urgency, Hong’s essay collection managed to unearth so many dormant feelings, or what she describes as minor feelings: “the racialized range of emotions that are negative, dysphoric, and therefore untelegenic.” In the book’s afterglow, I felt newly legible, as if I’d been given a language through which to speak. But that language was also inherently intricate and porous, providing just as many questions as it did answers.

I wanted to know, for instance, how other Asian Americans felt about Hong’s forceful assertions about race.

“Within the popular imagination,” she writes, we “inhabit a vague purgatorial status: distrusted by African Americans, ignored by whites, unless we’re being used by whites to keep the black man down.”

I wanted to discuss Hong’s relationship to the comedy of Richard Pryor, which unexpectedly filled the daughter of Korean immigrants with “a shock of recognition,” urging her to reexamine her relationship to poetry. And while the book only scrapes the implications of queerness—Hong mentions the writer Ocean Vuong and the performance artist Wu Tsang, who is trans—I wanted to further explore, with other queer folks, how being queer and Asian complicates Hong’s notion of minor feelings all together.

I took all of these feelings to—where else?—Instagram, where I posted a photo of Minor Feelings next to other books I’d recently read, asking people if they wanted to start a book club for queer and trans people of color. I wasn’t particularly optimistic because, with a few exceptions, rarely did I talk to my friends about books. It was so much easier to discuss the newest documentary on Netflix.

In the age of Grindr, Instagram, and Twitter, who had time to read books anyway? Mentioning books felt like the conversational equivalent of a dusty pair of monocles.

To my surprise, the post received an enthusiastic number of responses, which essentially amounted to “👍🏽👍🏽👍🏽” and “MEEEE” from both friends and strangers. It was enough to make me reach out to a writer friend to ask: “Should we start a queer book club?!”

But first, the anxiously curious journalist in me had so many questions, from how to put together a proper group to how to select books for discussion. I answered them by reaching out to a handful of book club organizers in New York, Toronto, and Washington D.C. Some of the book clubs, like that of Andreas Joshua in Brooklyn, are open to straight people.

“I wanted it to be all-inclusive,” says the founder of The Aphrodisiac Kitchen, a queer food journal, who notes that all the members of his group are “queer adjacent,” including a straight woman with a lesbian mom.

Others, like Farrah Skeiky and her book club in D.C., explicitly cater to queer and nonbinary women of color. The photographer and creative director was inspired by popular social media accounts like Well Read Black Girl and Noname, which she saw “radicalizing the book club concept.” She isn’t sure if she wants to expand her book club to Instagram, “but I do know that I have people in my immediate community who want to feel more engaged with the people around them and the things they are reading, and they needed a place to start,” she says. “This is a place to do that.”

Find a Good Name

Gays love puns, especially the literary types. Selecting a good name can set the tone for your book club. Farrah named her book club for queer and non-binary women of color Fenty Book Club, a nod to Rihanna’s inclusive makeup line, “because there’s a shade for everybody,” she says. In Toronto, James Resendes, after personally committing to only reading books by queer writers, decided to start a book club called Gay Writes, while David Vazquez, a field engineer in New York, inherited the name Read or Be Read from the longstanding club he rebooted in 2019.

“It’s not a name I would have chosen,” David says. “I think it comes off as a little antagonistic. Even though it’s true—there have been readings where people have decided to come without finishing the book.” Andreas, who hasn’t yet formally named his book club, threw around the joking title Faggots Who Read Their Friends, but he wanted something more serious. “I need to come up with one,” he says, “because I would like to start doing a flyer for it.”

Make New Friends, and Maybe More

Book clubs are a good way to keep in touch with old friends outside of meetups at bars and nightclubs. They’re also an ideal way to make new friends or even meet potential partners, as the clubs expand by word of mouth. “We’ve had one couple that met through book club,” David says. “They were two friends of mine. I noticed that they started canoodling after the meetings, and one thing led to another. They’ve been together for two years now.”

In terms of size, 10 to 15 members strikes a sweet spot for lively yet intimate book discussions, though Gay Writes, which James publicly hosts at Type Books, an independent book store in Toronto, often attracts somewhere between 20 and 25 attendees. “Not everyone is clamoring to speak at every meeting,” he says. “I value these people in particular because they come with a strong desire to learn and to belong. I love when people haven’t read the book and yet come anyway to be with the group and hear what others thought about it—that’s exactly the sense of community that I was striving for.”

Create Access

Hovering around $30 for a hardcover, books aren’t cheap. For this reason, James favors books that are available in paperback and avoids books that are out of print or difficult to source. (Also, friendly reminder: Check your local library.)

Farrah of Fenty Book Club provides the following options to obtain the literature in her monthly newsletters: A.) I’m not sure if I can afford to buy a book. B.) I am willing to buy a book for a fellow reader who can’t afford one. “No one has to really know who is donating or who is getting the book,” she says, emphasizing the anonymity of the emails. “So any of that stigma can be removed.” She also includes page numbers when presenting books for vote via email, seeking out those that feel approachable to read. “We don’t have to go through a huge tome every month,” she says. “We can do e-books, we can do chapbooks, we can do essay collections.”

Everyone I spoke to emphasized the importance of maintaining a communal ethos, particularly when it comes to selecting books. Each meeting, Andreas gives everyone three scraps of paper to write down the books they want to nominate and then mixes them into a cup. The group votes for one of three randomly selected choices to determine the book they’ll read next month.

Define Queer

How queer the books are varies from group to group. Sticking to the theme of her club, Farrah’s group only reads books by queer and non-binary women of color. David’s group, on the other hand, keeps a “pretty broad” definition of queer. “When we chose Parable of The Sower [by Octavia E. Butler] we thought the fact that one of the characters is a woman who, for a lot of the book, identifies as a man for the sake of her own security—and also because the author was asexual—fell within our realm of queer,” he explains. “We also thought the alien relationship dynamics described in The Long Way to a Small, Angry Planet [by Becky Chambers] was queer because they depicted aliens that changed gender and discussed polyamorous species.”

Stay Organized

How you communicate with members depends on the nature of the group. Because Gay Writes is hosted publicly at a bookstore, James updates information through the club’s Instagram page. Farrah’s group prefers email, which tends to take on the vibe of a community newsletter, including recommendations for podcasts, playlists, and literary events at local bookstores. David communicates with members via a Facebook group. While Andreas, bravely, uses a group text, he’s clear about setting boundaries: “We’re very respectful in the group text message. We don’t text each other all the time. If we’re texting, it’s of purpose.”

Reading Recommendations

The Faggots and Their Friends Between Revolutions (1977) by Larry Mitchell

“It was a really important reminder of what community actually means and not this commodified bullshit we’re being fed. People really enjoyed that. It’s so fantastical, and a short, easy read for people. It felt really relatable for everyone. That was definitely the hit right there.”

—Andreas Joshua, Brooklyn

In the Dream House (2019) by Carmen Maria Machado and White is for Witching (2009) by Helen Oyeyemi

“For very different reasons. We all absolutely loved Carmen’s memoir, and there was so much in there about abuse and the queer narrative to unpack. It was just exciting to see how this story resonated across the spectrum of our group and how much they had to say about it. In contrast, the group was pretty split about how we felt about Helen’s gothic fairytale when we began. We spent half of the meeting just trying to figure out what was actually happening in this maze of a story, and the other half deciphering what it all meant. But what was most inspiring was the way that the discussion changed people’s opinions by the end—it was our most lively and engaging meeting to date, clocking in at over an hour and a half in length.”

—James Resendes, Toronto

I’m Telling The Truth, But I’m Lying (2019) by Bassey Ikpi

“A really great collection of essays about a Nigerian American woman’s experiences with being bipolar, before, during and after her diagnosis. We had really intense discussions about mental health in immigrant African American communities. I remember asking people what essays were hanging around their brains the most, and kind of letting conversation go from there, which was great because if you had read just one or two essays you would have an answer.”

—Farrah Skeiky, Washington D.C.

Parable of the Sower (1993) by Octavia E. Butler and Call Me by Your Name (2007) by André Aciman

“One of two things makes for an interesting discussion: Lots of differing opinions or relevance. Parable of the Sower was a book from the ’90s that honestly feels like it should be written today. It’s probably more poignant and meaningful. Call Me By Your Name was probably one of the most divisive books we read. People loved it. People hated it. There was a lot of yelling.”

—David Vazquez, New York