In the 1990s, a group of Hawai‘i citizens stood up for their equal rights and pioneered a movement. But, most high schools aren’t teaching this important part of social history.

Text by Kylie Yamauchi

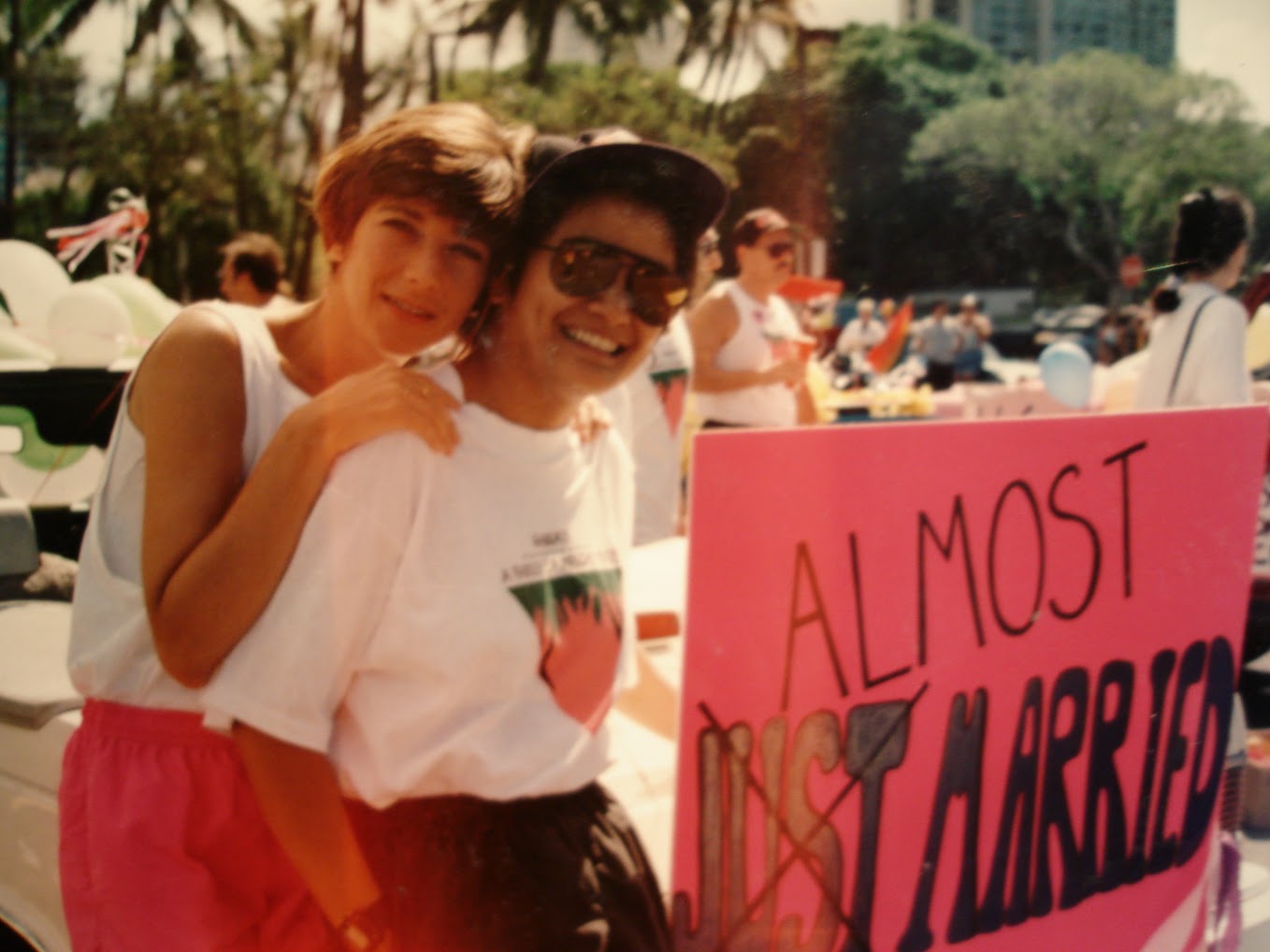

Images courtesy of Genora Dancel

I didn’t learn about Baehr v. Lewin, the Hawai‘i state lawsuit that sparked the marriage equality movement nationwide, until I took a college course on LGBT history in my early 20s. You would think being from Hawai‘i, I’d have learned about it sooner because what place wouldn’t want to claim itself as the origin of this landmark case? (Not this time, San Francisco!) Who wouldn’t want to boast of the influence a remote archipelago in the Pacific had on the rest of the United States? (Take that Jeff Sessions!)

As it turns out, the liberal state has its reservations about discussing LGBT history in high school classrooms, a result of systemic homophobia on a national level. Anti-LGBT curriculum laws, informally called “No Promo Homo,” exists in at least eight states. Although Hawaiʻi is not one of these states, some of its high schools, usually of religious backgrounds, follow protocols that avoid discussing LGBT subjects, which means history like Baehr v. Lewin is rarely shared in the classroom.

The story of Baehr v. Lewin begins on December 17, 1990, when three same-sex couples—Genora Dancel and Ninia Baehr, Tammy Rodrigues and Antoinette Pregil, and Pat Lagon and Joseph Melilio—walked into the Hawaiʻi State Department of Health and asked for marriage licenses, which were afforded only to couples of the opposite sex at the time. The result of their visits were expected: They were denied. The couples had reason to be incensed, but they calmly accepted the clerk’s refusal; they now had reason to file a lawsuit against John Lewin, the director of the DOH.

In the complaint, attorney Dan Foley argued that the DOH’s treatment of the plaintiffs denied them equal protection of laws and due process of laws. Despite this approach, the lawsuit had no impact in the circuit court and was dismissed with a half-glance. It seemed as if Baehr v. Lewin had taken a similar fate to its predecessor Baker v. Nelson, the 1972 Minnesota lawsuit that challenged the denial of a marriage license to a same-sex couple, and would disappear into oblivion with other LGBT efforts. But history decided to take a different course, as it sometimes miraculously does.

On September 23, 1992, the bench memo for Baehr v. Lewin landed on the desk of Steven H. Levinson, Associate Justice of the Hawaiʻi Supreme Court, for reconsideration. Levinson’s written response stated that “the burden will rest on Lewin to overcome the presumption that HRS § 572-1 [requisites of valid marriage contract] is unconstitutional by demonstrating compelling state interests and is narrowly drawn to avoid unnecessary abridgments of constitutional rights.” His court opinion was the first of its kind to propose that the ban on same-sex marriage was unconstitutional. It was a gutsy move for a justice only appointed in April of that year to release an opinion that countered the opinions of his fellow associate justices and challenged the state of Hawaiʻi. But his action gave the marriage equality movement a valid, legal argument to stand on. The small island state, known for its aloha spirit and seen as a paradisiacal escape from the mainland, proved to be a strong political force and in later years remained a center for LGBT politics, recently passing a law that protects LGBT minors from conversion therapy. “This little grain of sand out in the middle of the big water got the marriage equality movement rolling,” Levinson says. “The waves emanated from this rock around the world.”

But waves come in sets. The next two decades consisted of promising wins met with overturning losses. After the state failed to disprove Levinson’s claim, Honolulu Circuit Court Judge Kevin Chang found in favor of the plaintiffs and ended the ban on gay marriage in 1996. But shortly after, in 1998, the Hawaiʻi Constitutional Amendment 2 was passed by the majority of voters, legally defining marriage as exclusively for couples of different sex. “Overall, you have to take the good with the bad,” says Dancel, one of the original plaintiffs in the case. “People had to sort this [news about Baehr v. Lewin] out in their lives. But at least we got them to start discussing the possibility of same-sex marriage in this country.”

Back in 1990, three same-sex couples from Hawaiʻi were willing to fight for marriage equality. On June 26, 2015, a majority of the nation rallied together in celebration of the U.S. Supreme Court’s ruling that recognized same-sex marriage as a fundamental right. But the journey to this momentous win is unknown to many. Perhaps, if I and others from my generation had learned about this history in our education, we could have been celebrating much earlier.